Tesco, Britain’s largest grocer, has been having a hard time lately. Last September it had to admit to overstating its net profits by £250 million. Then in October it announced a 4.4% drop in mid-year sales, a 91.9% drop in net profit, and an increase in the profit overstatement to £263 million.

Tesco, Britain’s largest grocer, has been having a hard time lately. Last September it had to admit to overstating its net profits by £250 million. Then in October it announced a 4.4% drop in mid-year sales, a 91.9% drop in net profit, and an increase in the profit overstatement to £263 million.

Right after that the chairman stepped down, Tesco dismissed eight senior managers, and the British government began an investigation into the company’s financial reporting. The share price plummeted, the rating agencies put the company’s credit rating on review for a downgrade, and the company cancelled the syndication of a £3 billion revolving credit.

A damaged model

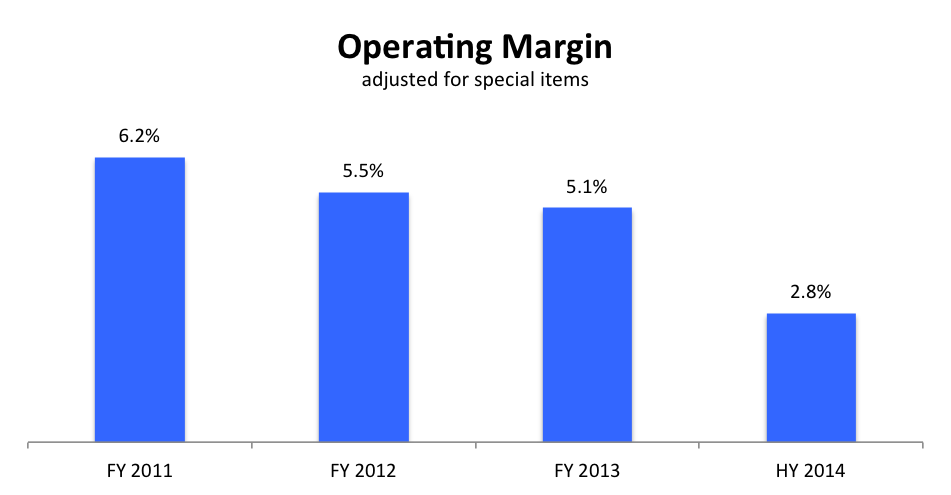

Tesco’s problems go much deeper than an earnings shortfall, accounting anomalies, and a management shake-up. It has fundamental problems with its business model. Tesco’s business is built for size not speed, but it’s facing very lean, agile competitors.

It’s the third largest retailer in the world, behind Wal-Mart and Carrefour, and it’s the UK’s grocery giant. Tesco has twice the market share of Asda, its next biggest competitor. Size matters: it gives Tesco bargaining power with suppliers, customers, regulators, lenders, and investors, driving profitability and profit growth.

But with size comes complexity. To reach as many customers as possible, Tesco uses seven different store formats in the UK, ranging from giant hypermarkets to small convenience stores. Its stores carry as many a 40,000 different inventory items, about 50% of them from major brands and the rest under Tesco’s private labels. It also has other businesses, including digital tablets, coffee shops and restaurants, online retailing, and banking.

And with complexity comes costs. With so many different stores and product lines aimed at so many different consumer segments, it’s difficult for Tesco to gain economies of scale across all its operations. Purchasing, logistics, and merchandising vary a lot by business line, store type, and location.

Contrast Tesco’s model with Aldi’s, one of the UK’s leading discount grocery chains. Aldi is small; it has a fraction of Tesco’s market share. But what Aldi lacks in scale it makes up in efficiency.

Aldi’s supply chain is as streamlined as a Formula 1 racing car. It has only two types of store, a medium-size market and a convenience store. A typical Aldi supermarket stocks no more than 1,500 products, and Aldi buys and ships them in shelf-ready packaging for display in the store.

Aldi’s labor costs are low: its stores have just two or three staff working at any time. Customers bag their own purchases and pay a deposit for shopping carts, so staff aren’t busy bagging groceries or collecting carts from parking areas. Shelf-ready shipping and fewer products reduce workers needed to stock shelves.

Aldi passes on those savings to its customers. A recent study by Grocer magazine in the UK found that on a shopping basket of 33 items Aldi was 16% cheaper than Asda, 20% cheaper than Tesco, and 40% cheaper than Waitrose.

Lured by low prices, consumers switched to discounters like Aldi during the recession that hit England in 2007, and they’ve kept on switching. Unable to match discounters in efficiency or in price, Tesco watched its market share peak at 31.7% in 2007 and fall steadily to reach 28.7% now, while discounters’ combined market share climbed from 4.7% to 8.4%.

Damage control

What can Tesco do about all this? A restocking of management seems in order, and that’s just what the company has done. Philip Clarke, CEO since 2011, was replaced by David Lewis in September of this year, and Richard Broadbent, Chairman since 2011, is leaving with no replacement named yet.

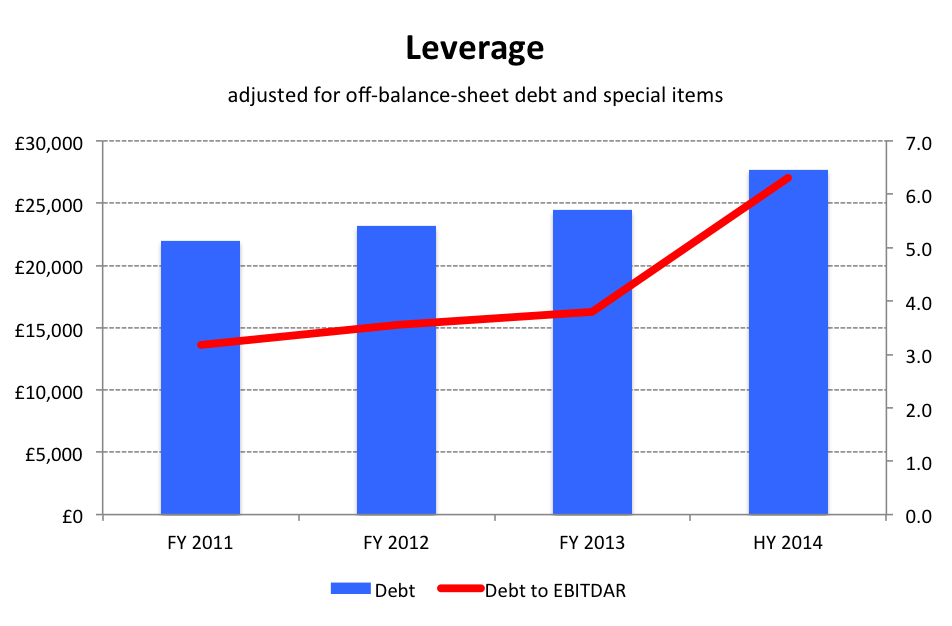

David Lewis has laid out his priorities for Tesco: focus on the business in the UK, strengthen the balance sheet, and restore the company’s reputation. Just how he plans to counter the discounters is unclear, but he has to find a way to cut costs and regain share. That won’t be easy, and it likely will take a basket load of capital spending.

Finding that capital may be difficult. Tesco’s financial leverage is already high, with debt to EBITDAR at 6.3x fully adjusted for operating lease debt equivalents and pension deficits. Moody’s downgraded the company to Baa3 when the mid-year results came out, pushing the rating to the brink of junk status.

Rebuilding reputation may be harder still. Much depends on the results of the British government’s investigation into Tesco’s numbers. But more depends on changing the company’s culture, which could prove as stubborn and unwieldy as Tesco is big and complex.

Lewis also may find the culture at Tesco more fearful than responsive. Previous CEOs were famously demanding, and the penalties for not meeting growth and profitability targets could be severe. Philip Clarke got out the long knives and fired 50 executives in August 2013, after Tesco’s annual profits fell for the first time in 19 years.

Managers more worried about their jobs in the short term than the company in the long term, won’t risk making changes. They might not even risk telling the truth and succumb to the temptation to overstate their units’ results instead. Tesco may be facing as many challenges from itself as it does from its competitors.