A few days ago Tesco announced its worst full-year loss ever and one that ranks among the biggest in the history of British business — £6.4 billion. The company took a cart load of special charges to account for three years of declining sales, profits, and cash flows and a financial reporting scandal. It also disclosed uncomfortably high leverage (adjusted debt to EBITDAR of 7.4x) and limited amounts of liquidity (a liquidity position of £3.4 billion).

A few days ago Tesco announced its worst full-year loss ever and one that ranks among the biggest in the history of British business — £6.4 billion. The company took a cart load of special charges to account for three years of declining sales, profits, and cash flows and a financial reporting scandal. It also disclosed uncomfortably high leverage (adjusted debt to EBITDAR of 7.4x) and limited amounts of liquidity (a liquidity position of £3.4 billion).

There are signs Tesco is getting better. It cut prices, improved service, laid off staffers, closed stores, and agreed to start funding its pension deficit. Customer traffic and purchases in the UK are growing again, and the rate of sales decline there slowed to (1.0%) in Tesco’s fourth quarter.

Tesco’s CEO “Drastic Dave” Lewis made a lot out of this, saying, “They are pretty good vital signs,” and, “This patient is OK.” But he may be discounting his company’s immediate tactical problems. Worse, he may ignoring a long-term strategic threat.

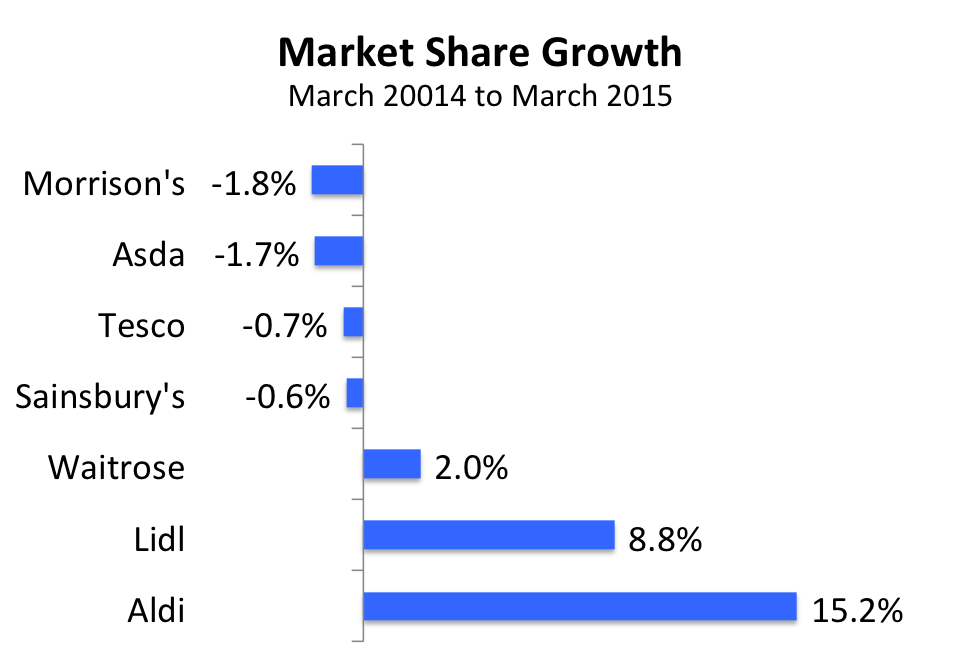

Tactically, Tesco is still in retreat. Discount grocers Aldi and Lidl are capturing more and more share from Tesco and the other mid-market chains in the UK. And they’re gaining at a growing rate.

We don’t think Lewis is trying to transform Tesco into a low-cost, low-price chain and win back lost market share. He’s trying to hold on to a core set of customers who prefer Tesco’s variety and convenience. He understands he has to shrink to a cost base that supports that still-big but smaller business.

His plan may succeed in the short run but fail in the long run. This has to do with something we call the incumbent’s dilemma, borrowing freely from Clay Christensen’s research on innovation. It’s the reason so many successful companies fail to respond to competition from new entrants.

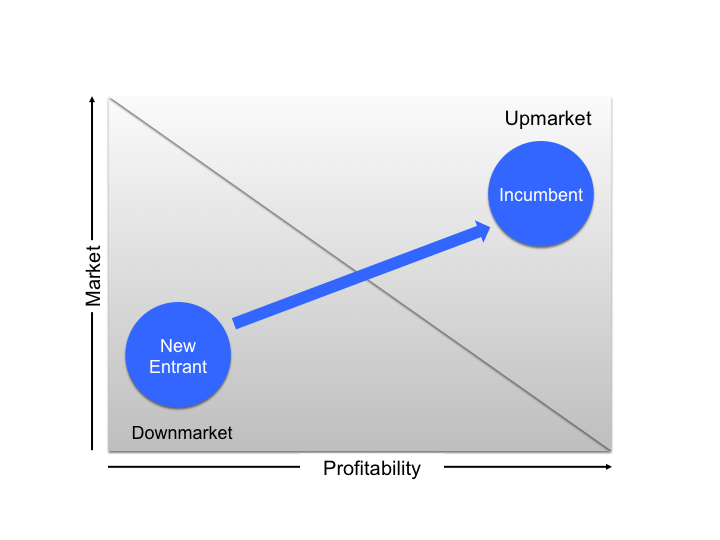

The part of an industry where demand is uncertain, segments are small, and margins are low is Downmarket. That’s where new entrants start competing, and it’s where Aldi and Lidl started in the UK. Incumbents are Upmarket, where demand is more predictable, volumes are higher, and so are margins. It’s where Tesco was five years ago.

The part of an industry where demand is uncertain, segments are small, and margins are low is Downmarket. That’s where new entrants start competing, and it’s where Aldi and Lidl started in the UK. Incumbents are Upmarket, where demand is more predictable, volumes are higher, and so are margins. It’s where Tesco was five years ago.

If new entrants are successful, they get more resources, improve their capabilities, and start to move upmarket, drawn by higher growth and profits. That’s what Aldi is doing now, adding more fresh foods and premium products like caviar, fresh crab, and fresh scallops to lure wealthier shoppers. It’s also adopting a new, larger store format.

Over time, new entrants can end up competing directly with the original incumbents in the upmarket segments. That’s what happened in steel, autos, and airlines. For reasons we talked about in an earlier post, it’s very hard for big, successful companies to meet such a threat.

Drastic Dave needs to be very, very worried that it is happening in the grocery business in the UK as well. And be terrified Tesco won’t be able to keep Aldi and Lidl downmarket or compete with them when they arrive upmarket, where Tesco was so secure for so long.

Tim, thanks for this very interesting series on Tesco. A couple of points that bolster the pessimistic case:

1. In my experience financing LBOs of grocery chains, the rigidity of fixed costs in distribution and marketing is the most serious challenge. A decline in sales hits doubly hard when you can’t cut these costs to meet it. Once a store starts declining due to new and better competitors in the market, it spirals down quickly and cost-cutting moves only hurts its product and customer service quality. Also, shedding assets to cut costs is best done when you have time. Having to liquidate real estate in a hurry really destroys value.

2. Don’t count on Aldi being unable to go upmarket. As their ownership of the Trader Joe’s chain in the US shows, they thoroughly understand a variety of merchandising styles and can easily meet the needs of almost any market segment.

A fine series of articles. I financed several supermarket LBOs in the 1980s. Once a merchandising style no longer attracts customers, stores lose money in a “death spiral” as everything one does to save operating expenses makes the store less attractive to shop in. The owners and managers of ALDI are also expert at upmarket merchandising, as shown by their success with the Trader Joe’s chain in the US.

Also, as we have seen with Sears/KMart and JC Penney in the US (and at least one disastrous loan I made once), it is very difficult to turn around a retailer when one is capital constrained. If I were Mr. Lewis, I’d be selling off assets to raise capital which would be used to reduce the debt burden and to rejuvenate the stores worth keeping.