On January 8 Tesco annou nced more details of its plan to improve its competitive position in the UK, revive its profitability, and bolster its finances. It’s going to cut prices on popular brands, trim £250 million in operating costs, limit capital spending, stop the dividend, and sell assets.

nced more details of its plan to improve its competitive position in the UK, revive its profitability, and bolster its finances. It’s going to cut prices on popular brands, trim £250 million in operating costs, limit capital spending, stop the dividend, and sell assets.

Some of the changes may already be working. The decline in UK sales is easing, with growth going from (5.4%) in the second quarter to (2.9%) in the third quarter to (0.3%) during the Christmas season.

But January 8 brought more bad news as well. Moody’s downgraded Tesco’s credit rating to junk status (Ba1), and Standard & Poor’s did the same a few days later (BB+). Both agencies cited competition, profitability, and financial leverage as the reasons. Those are the risks we discussed in our January 5 blog post, “Testing Tesco.”

But we think the rating agencies understate the risks. They don’t consider the difficulty of changing a company as large and as focused as Tesco. We see Tesco’s still unresolved financial reporting problems as symptoms of a damaged corporate culture that is likely to fight hard against change.

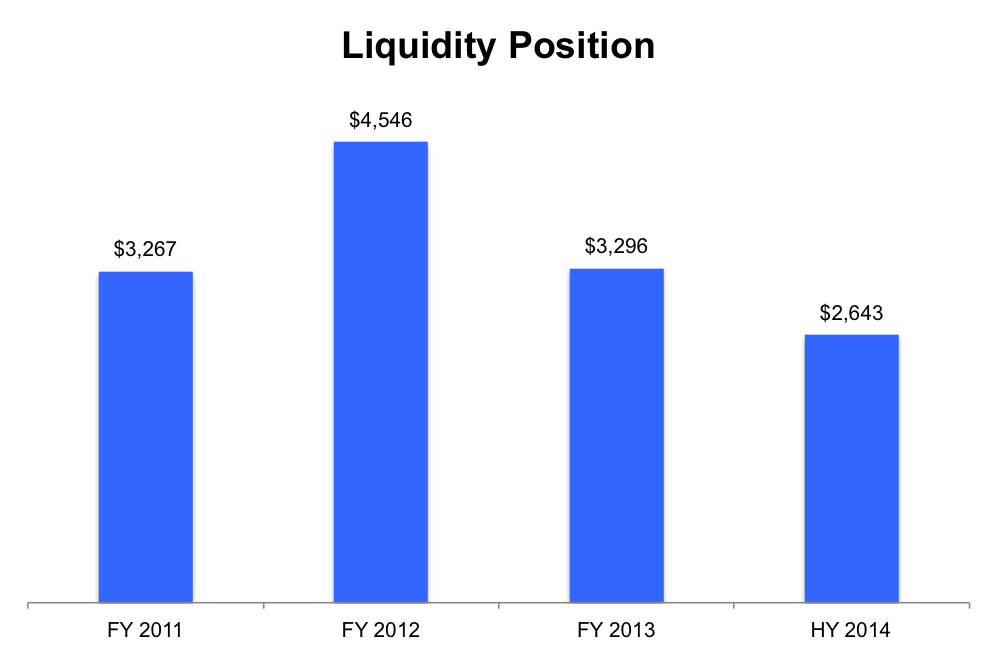

The agencies don’t mention liquidity in their concerns about Tesco, but the declining trend in liquidity worries us at least as much as the increasing trend in leverage. The company’s liquidity position is at a four-year low, driven by growing current debt levels.

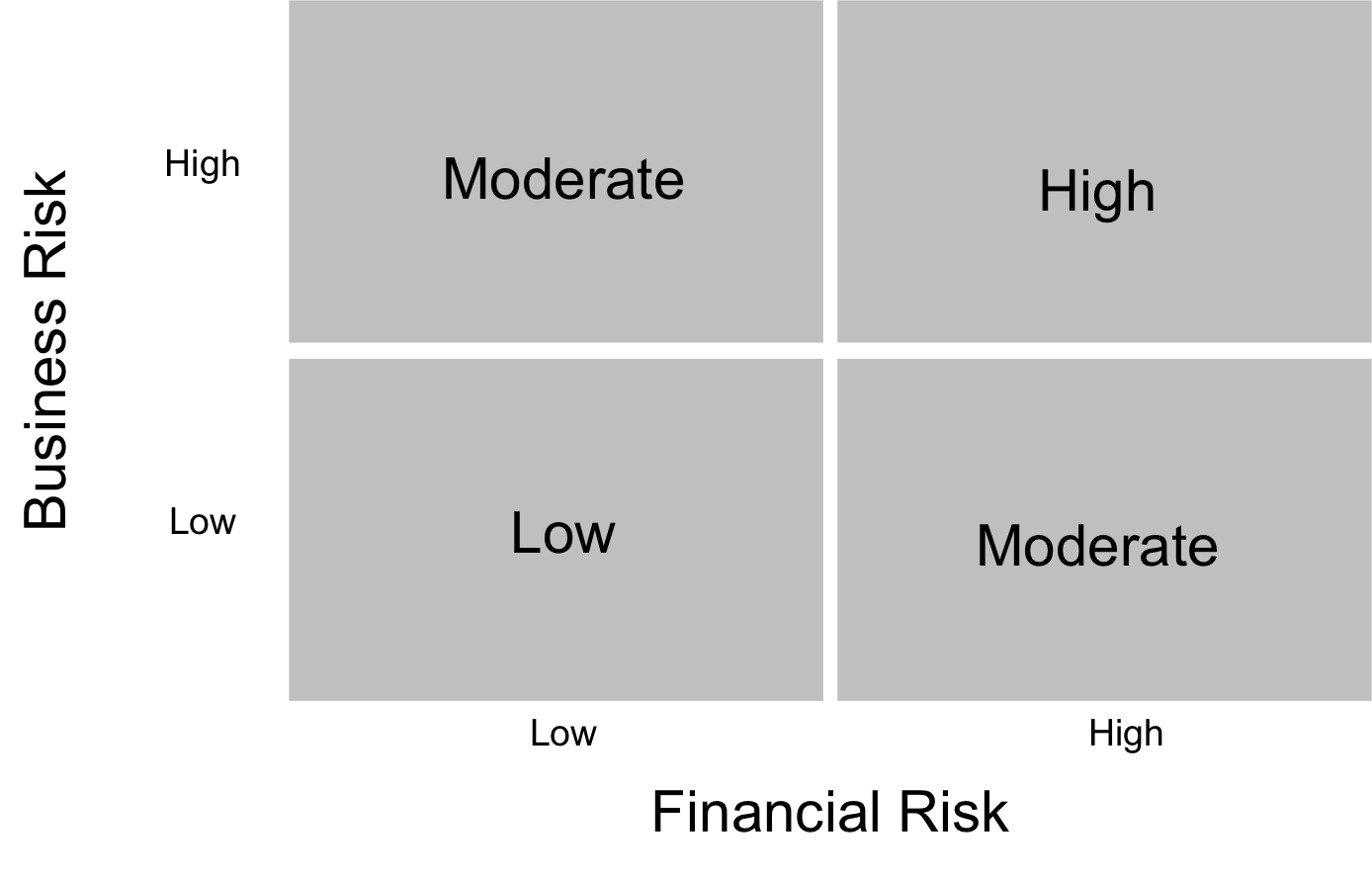

But our biggest worry isn’t any single risk or even the number of risks. It’s the compounding effects of Tesco’s risks, the way the company’s business and financial risks amplify one another. It’s common to think of credit risk in two dimensions, business risk and financial risk, with the amount of either risk ranging from low to high. Put in a graph it looks like this.

High business risk means some combination of high cyclicality, intense competition, weak competitive position, poor operating results, and unrealistic business strategy. High financial risk means high leverage, low liquidity, limited financial flexibility, and an aggressive financial strategy.

Any of these risks can be a problem. But companies get into real trouble the same way airplanes, oil rigs, and armies do, not from a single problem but from a combination of them. They are far more likely to be in distress when business and financial risk are both high.

Five year’s ago Tesco was in the the lower left-hand box, and as it lost share to discounters over the last few years it moved into the upper left-hand box. During that same period it took on more and more debt and operated with less and less liquidity, pushing itself into the upper right-hand box. And that’s a place no company should be.

To get out of the box Tesco needs to act against the risks it has the most direct control over. It needs to bring down leverage and drive up liquidity. In our next post, we’ll talk about how Tesco can do that.