Under pressure from rising interest rates, soaring inflation, and growing government debt, the Argentine peso has crashed in the last few weeks. The government is asking the International Monetary Fund for a credit facility of up to $30 billion to help cover imports and debt service and support the peso. Only a year ago, when it issued $2.8 billion in hundred-year bonds, Argentina was the darling of the international debt markets; now it’s the dog. To understand why, you have to understand that the debt markets remember Argentina’s default in 2002, the biggest in history.

Under pressure from rising interest rates, soaring inflation, and growing government debt, the Argentine peso has crashed in the last few weeks. The government is asking the International Monetary Fund for a credit facility of up to $30 billion to help cover imports and debt service and support the peso. Only a year ago, when it issued $2.8 billion in hundred-year bonds, Argentina was the darling of the international debt markets; now it’s the dog. To understand why, you have to understand that the debt markets remember Argentina’s default in 2002, the biggest in history.

The problem

For Argentinians in 2001, the defining economic experience was the misery of the 1980s. In a series of deep recessions, the economy shrank by 17% in real terms between 1981 and 1990. To support the faltering economy, the government borrowed heavily and aggressively expanded the money supply. Consumer price inflation soared from a painful 101% a year in 1980 to an excruciating 2,314% in 1990 and at times was even higher.

In 1991 the government put in place a new plan to get back to growth and tame inflation. The value of the Argentine peso was set at par to the U.S. dollar, with the guarantee that pesos could be freely converted to dollars. The Argentine central bank was required to ensure convertibility by holding currency and commercial bank reserves in dollars.

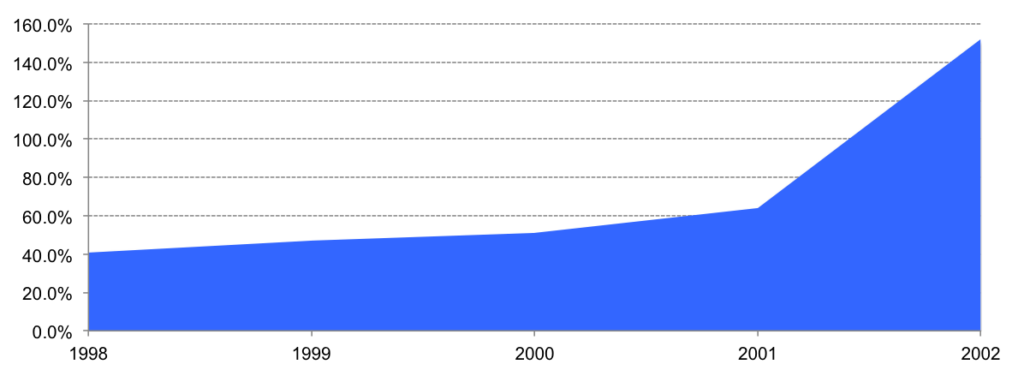

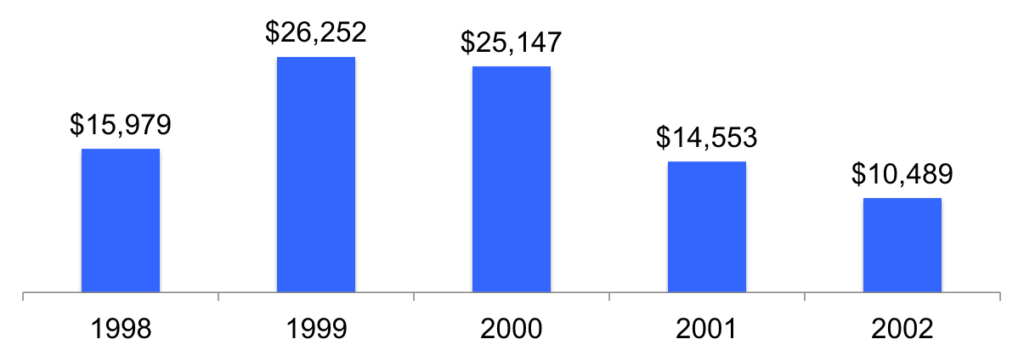

It worked. The economy grew by 63% from 1990 to 1998 in real terms. The government ran average spending deficits of 1.7% a year between 1992 and 1998, driving debt from 26% of gross domestic product (“GDP”) in 1992 to 35% in 1998. But tied to the dollar, the money supply grew at a restrained rate, and inflation fell to 1.7% in 1998.

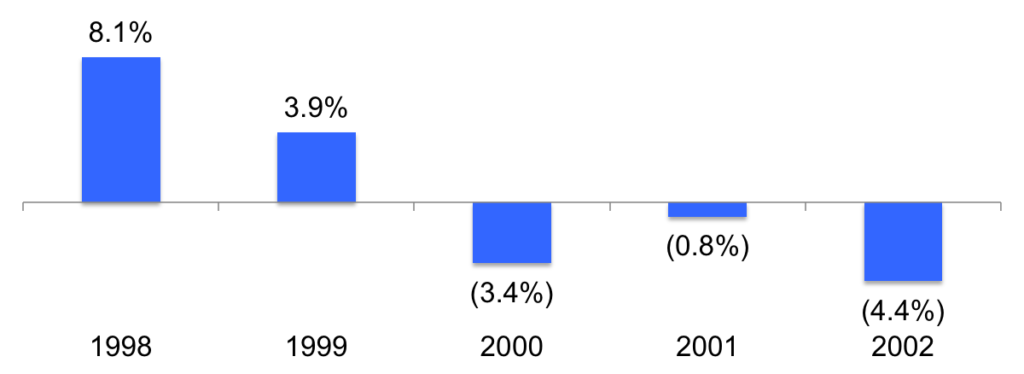

GDP growth

Exports were almost 10% of the Argentine economy in 1999, and almost one third of them went to Brazil. When Brazil gave up its currency’s link to the U.S. dollar and devalued the real by 40% against the dollar in 1999, Argentina kept the peso pegged to the dollar. The price of Argentina’s exports to Brazil jumped sharply and their volume fell. Total exports fell by 1.3% in 1999, pushing Argentina into a recession in 2001.

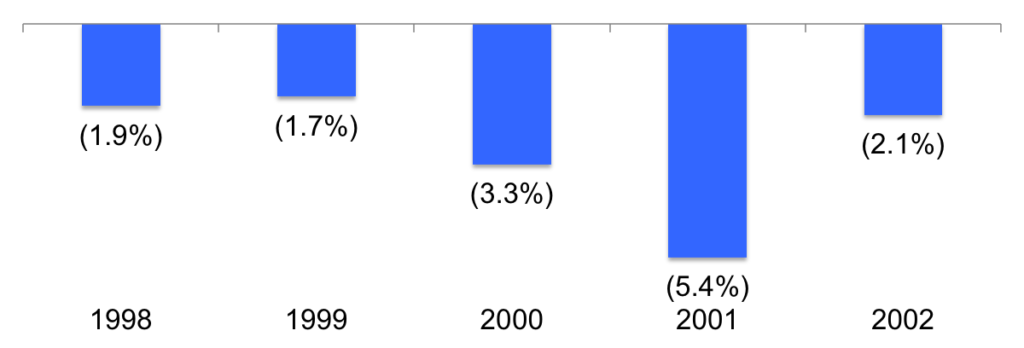

Budget balance

Tax revenues fell with the drop in business and consumer incomes in the recession, but government spending did not. To make up the difference, the Argentine government borrowed in foreign debt markets, driving the ratio of public debt to GDP to 47% in 1999. But with Argentina’s budget deficit of only 1.7%, the dollar peg in place, and currency reserves of $26.3 billion, financial markets were not alarmed, and the risk spread on Argentine government debt was down 1.8% by year’s end.

Public debt

Argentina kept the peso pegged to the dollar in 2000, and the dollar continued to strengthen, making Argentina’s exports even less competitive. The government cut spending by $2.4 billion and raised taxes by $2 billion to try to reduce the fiscal deficit, but that only slowed the economy even more. By the end of the year, real GDP was down by 0.8%, the fiscal deficit reached 3.3% of GDP, and public debt to GDP climbed to 51%.

Argentine consumers and businesses along with foreign lenders counted on the dollar-peso peg. They feared another disastrous dive into hyperinflation if the government gave up on strict monetary discipline or let dollar reserves fall below payments on foreign debt and dollar deposits in Argentine banks. As government budget deficits grew and government borrowing increased, they became more and more worried about pressure on currency reserves and the peso.

The best estimate was that Argentina would need $22 billion per year to meet its external obligations over the next several years, including $14 billion in debt payments in 2001. To meet them, it had only $25 billion in currency reserves and a $14 billion stand-by credit from the IMF.

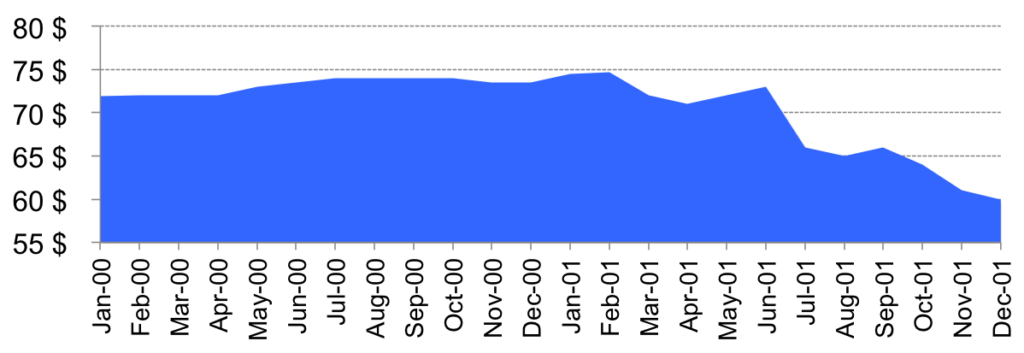

Risk spread

Foreign lenders began to charge a higher risk premium for loans to Argentina. The spread between interest rates on Argentine government debt and those on U.S. government debt increased to 7.7% by the end of the year. That drove domestic rates up to their highest level in three years.

The crisis

To keep the confidence of the debt markets in 2001, the Argentine government had to reduce borrowings. But cutting spending or raising taxes to shrink the deficit only cut deeper into economic growth. After two years of recession, with unemployment at 15% and more than 29% of the population below the poverty line, it was very difficult to get political support for more austerity.

That troubled foreign lenders, and the risk premium on Argentine sovereign debt reached 8% in February 2001. To avoid expensive foreign debt, the government sold $3 billion in bonds to Argentine banks, who already had 18% of their assets in government bonds.

Next, the government loosened the peso’s link to the dollar to spur exports. But that raised the possibility of an outright devaluation and a return to the disastrous policies of the 1980s. The foreign debt risk premium kept growing, reaching 10% in May.

Currency reserves

Currency reserves fell, as interest payments consumed more and more of the government’s financial resources. To avoid a default, Argentina restructured $29.5 billion of debt held by foreign investors. But the terms were tough; to postpone $12 billion in principal payments in 2001 through 2005, the government agreed to pay interest of 16% on the new debt it was issuing in exchange.

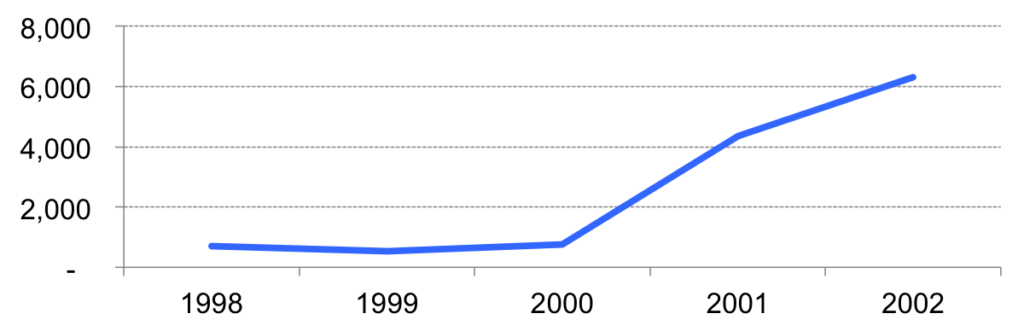

Bank deposits

Concerned about banks’ growing holdings of government bonds, which were approaching 27% of assets, depositors began withdrawing funds. System-wide deposits fell from a peak of $76 billion early in the year to $66 billion in September. High domestic interest rates were choking off economic growth, the fiscal deficit was getting bigger, and protests against spending cuts were growing.

Even though Argentina arranged another $8 billion in credit from the IMF, the risk premium widened to 16% by the end of September. That forced the government into another debt restructuring. It cut the interest rate on $55 billion in debt held by Argentine banks.

The risk premium on foreign bonds immediately shot up to 23%, and domestic rates soared to 80%. Currency reserves fell to $19 billion. Bank deposits fell by $2 billion in a single day and were down to $60 billion, as businesses and consumers transferred money offshore to protect themselves from bank failures and currency devaluation.

To prevent the collapse of the banking system and forestall a run-off in foreign currency reserves, the government limited withdrawals from domestic bank accounts and blocked money transfers abroad in December. That deprived the economy of liquidity, deepened the recession, and effectively ended the peso-dollar peg. The country’s risk premium rocketed to 430%. Unable to pay such high interest rates, the government of Argentina announced it was suspending payment on its foreign debt late that month, leading to a default early in 2002.

At the end of 2001, Argentina had $144.5 billion in sovereign debt outstanding. It owed $59.9 billion to domestic banks and other Argentine investors, and $84.6 billion to foreign lenders. Its foreign debt consisted of $58.5 billion to foreign investors in 152 bond issues in seven currencies and eight national jurisdictions and $27.9 billion to the International Monetary Fund and similar institutions.

The government began 2002 by cancelling the peso-dollar peg and devaluing the peso by 40% against the dollar to boost exports. It imposed a freeze on domestic interest rates to protect the economy. It also put restrictions on buying foreign currencies to avoid a runoff in currency reserves.

Argentina plunged into a recession. Real GDP fell by 4.4% in 2001 and 10.9% in 2002. Bankruptcies reached record levels in 2002. Unemployment rose to 23.6%, and 57.5% of the population was living below the poverty line by the end of the year. But growth in the money supply was restrained, and, although inflation reached 30.6% by year’s end, there was no repeat of the hyperinflation of the 1980s. Exports grew by 3.1%, and the current account balance for the year was positive.

The aftermath

Argentina remained in default through 2002. The government began working for a restructuring of its debt, aiming for a 70% reduction in principal, no repayment of past-due interest, and no payments at all to investors who refused to accept the deal. Negotiations continued until 2005.

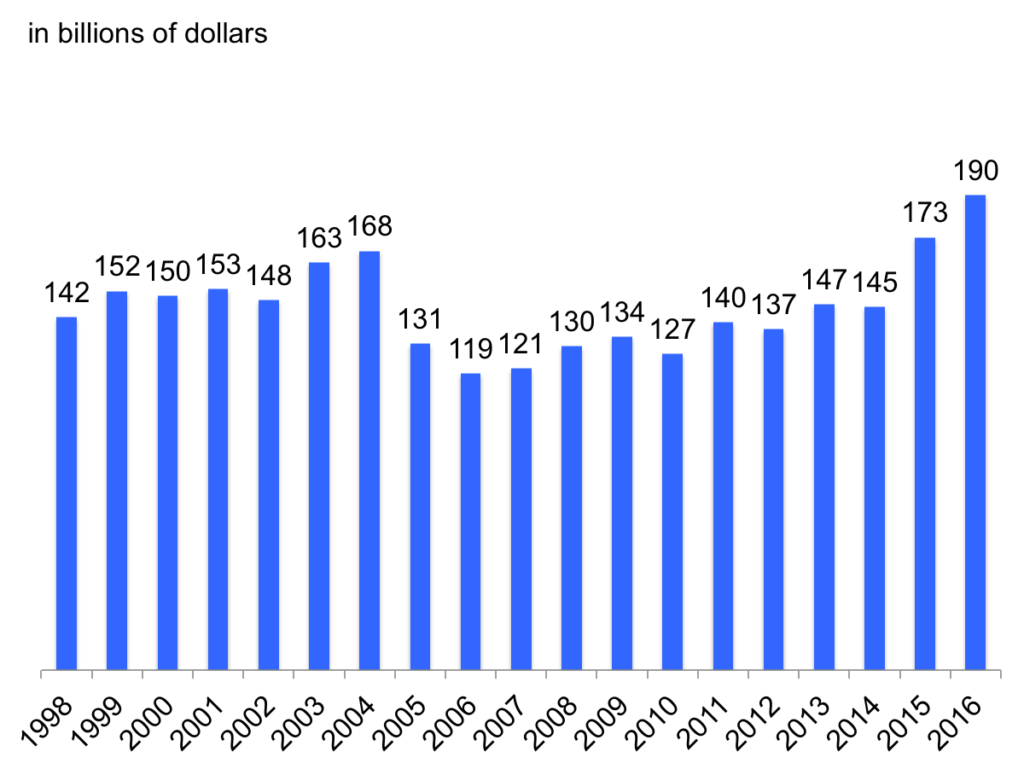

External debt

In that year’s restructuring, Argentina, facing more than 140 lawsuits in courts around the world, settled $63 billion of its debt at about 25% of the original par value. That was much lower than the recoveries in other sovereign defaults, which usually range from 50% to 60%. Argentina also repudiated $25 billion in unpaid interest on its debt.

Holders of 25% of the original bonds refused to accept the 2005 deal. Most of them settled in 2010 with recoveries similar to 2005’s. A stubborn few held out until 2016 and got recoveries worth about 40% of par. With that final settlement, Argentina was able to return to the offshore debt markets

With a government committed to economic reforms, Argentina issued $70 billion of external debt, including a record-breaking $16 billion bond issue in 2016 and a $2.8 billion 100-year issue in 2017. It’s that new debt burden that is making currency traders and bond holders nervous today.